The Second Death

What remains when the keepers of memory are gone

I come home exhausted after a day of cleaning out my mother’s house, getting it ready to sell. There’s an old box in my hand filled with my father’s writings, but I’m too tired to go through it. My son asks how it went and I tell him I feel a strange kind of grief, throwing away piles of things that were once meaningful like awards, certificates, even diplomas that belonged to my dad.

He thinks for a moment and says, “It’s like a second death. The death that happens when no one remembers you anymore.”

And I just stand there, yep. That one lands.

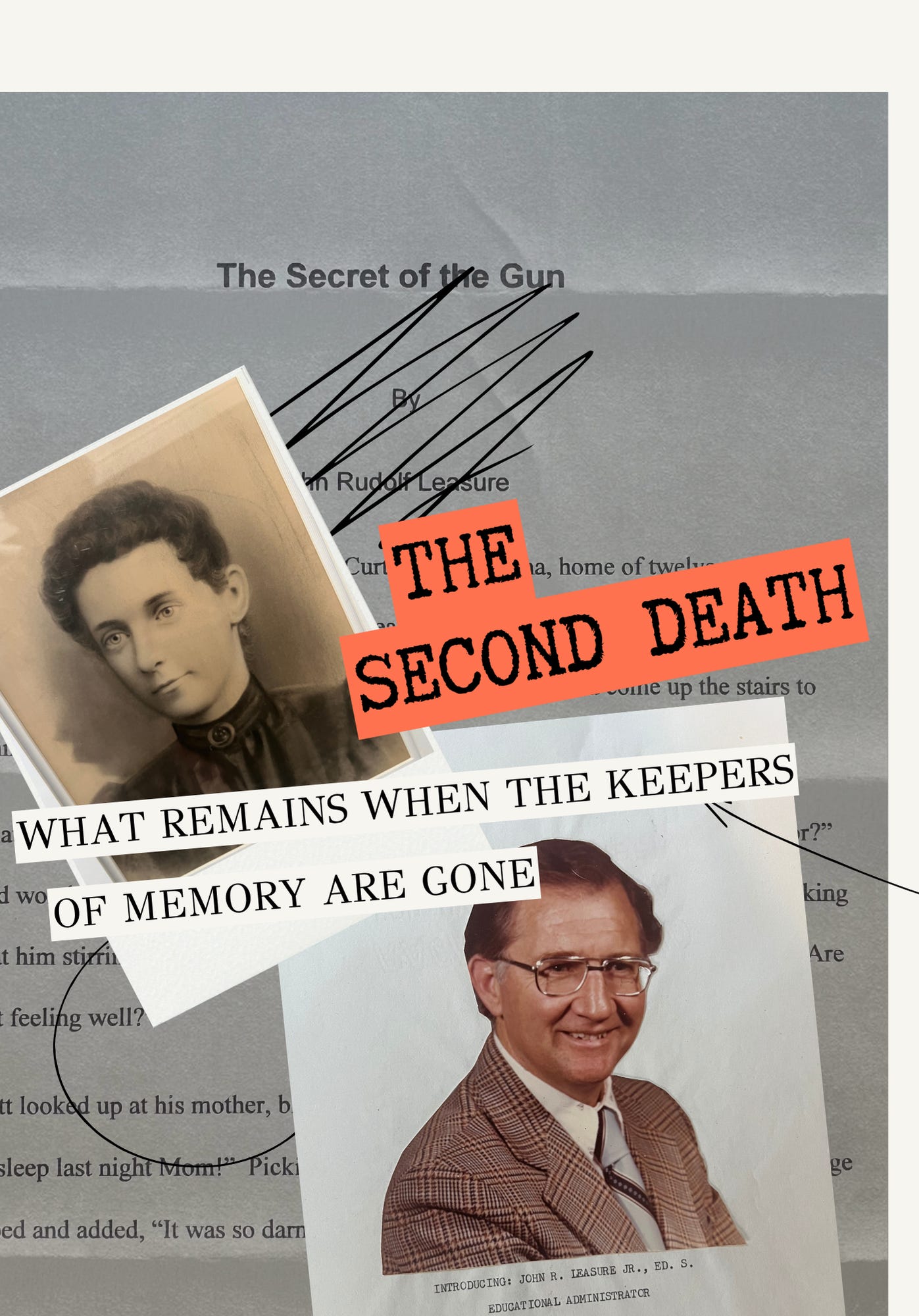

Later that night, I open the box. My father loved to write and I have stacks and stacks of papers, essays, typed on yellowing sheets of paper to go through. It’s like he was a hoarder of thoughts. And one by one, as I read, a person I never really knew starts to appear.

He wrote over fifty articles for education journals. Titles like Helping Your Child Become Less Critical of Others. In one, he writes: “We cannot isolate children from viewpoints, but we can teach them fairness and empathy.” It’s good advice for sure, practical, balanced its the kind of thing that would’ve made him a good principal. But the man who wrote it feels different from the man I knew. That version was older, more rigid, wrapped tight in Mormon duty. This one sounds curious, even gentle.

Then there’s a nostalgic piece called Remembering Bridgeville: The First Town Sold on the Internet. Apparently my parents lived there in the late 60s, raising my older siblings in this tiny, rural place with barely any electricity. He writes about loving the outdoors, the quiet. And I think: this man who loved nature, who took long walks, I never met him. By the time I came along, he was tired and the only thing I knew of him was the sermons and routines.

Some of the writings make me angry. There are these generic letters he wrote to family about blessings, testimonies, the same old lines. “Remember to pray. Go to church. Marry the right person.” I wanted a letter from him, not from a handbook on righteousness. Something that said he saw me, that I existed outside the mold. Reading those parts, I feel cheated, like there was a real father somewhere inside him who never quite made it to the page.

But then I find glimpses of him, sentences and fragments, where I can almost see the man behind the doctrine. And I feel this ache for the unlived possibilities between us.

I stay up late, long after everyone’s asleep, reading until my eyes burn. Apparently, he even wrote an entire novel! The Secret of the Gun. Never published, just tucked away. There’s something about that, the quiet futility of writing things no one ever reads, that feels holy. Like being a therapist, maybe: sitting with someone’s story, not to fix it, but to bear witness. To be the keeper of thoughts that might otherwise disappear.

Some of what I read I’ll share with my kids. Some I’ll keep to myself.

I don’t know if I care whether I’m remembered. The idea that everything about me might just vanish one day actually feels like a relief. But what hurts, what truly hurts, is knowing that when I go, the memories I hold of others will go too. That I am the last keeper of certain stories.

I’ve spent weeks deciding what survives: boxes of photos, nameless faces, cousins and great-aunts I can’t identify. Their faces stare out from fading prints, and I realize I’m the only one left who can say, they were here. But I don’t know their stories, and I don’t know who would even want to.

So I start letting go. One envelope at a time. Because what’s the point of keeping what no one will remember?

My son was right. There really is a second death, the one where memory fades, where names lose their anchor. And it’s heavier than I expected, because to keep someone alive, even just a little, you have to carry their weight.

And I’m tired.

Still, I save a few pages of my father’s writing, the ones that sound like him, or maybe like the man he wanted to be. I’ll keep them in a box with my own journals. Sometimes I imagine he’s still writing somewhere, a ghost hunched over a typewriter, trying to finish his thoughts.

And maybe that’s all legacy really is, the unfinished sentences we leave behind, hoping someone will care enough to read them.

This reminds me of a play I saw recently called "We Keep Everything", about a woman unpacking a stage filled with boxes and suitcases of memories of her Italian and Scottish grandparents. Things like a favourite tablecloth, a candelabra, old photos and video footage projected onto the stage, an old red cassette player playing her Nonna singing an Italian hymn.

As she unpacked everything, she decided what to keep and what to put back in the box, and it was a really beautiful show about grief, holding on, and letting go.

This piece you've written reminds me of that show, and I hope it was cathartic to write it.

I loved reading this so much. Thank you for sharing.